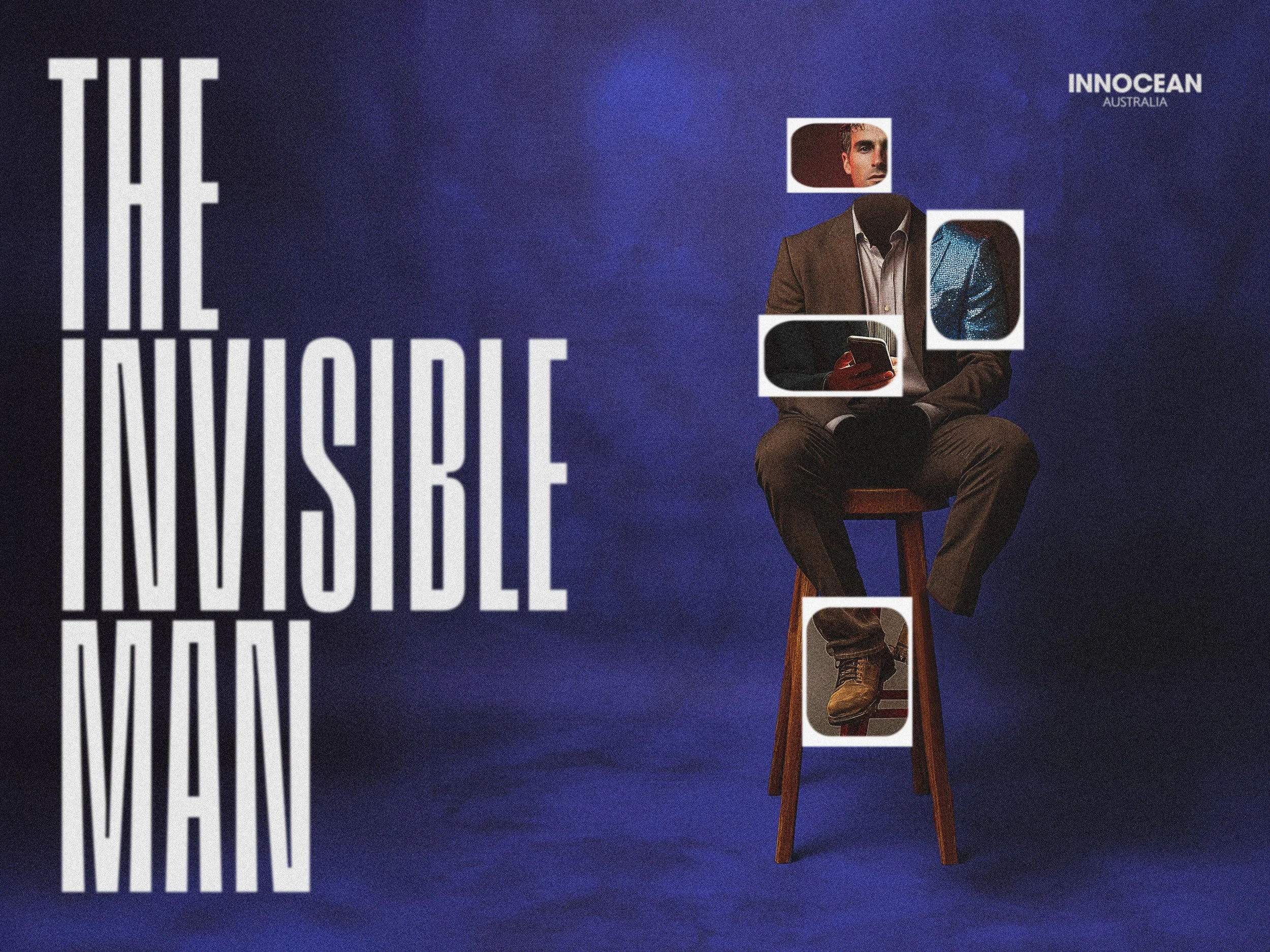

The Invisible Man

This International Men's Day, Innocean Australia's CEO, Jasmin Bedir, shines a light on 'The Invisible Man', the lack of conversations about masculinity, and why this is important for those who work in an industry that contributes greatly to pop culture, such as media and marketing.

Today is International Men’s Day. If you weren’t aware that there’s an International Day just for men, you’re not alone. In fact, of the men I asked, only a few knew it existed.

According to the interwebs, it’s a global awareness day for many issues that men face, including parental alienation, abuse, homelessness, suicide, and violence, but it’s also an occasion to celebrate boys’ and mens’ life achievements.

Still not feeling festive enough to put a boardroom event on? I don’t blame you. But depending on your gender, you may have different reasons.

If you’re a woman, there’s a chance you’re reeling from the news this year. We witnessed Australia’s Media reckoning with Channel 7 and 9 having their individual moments, but maybe not surprisingly resulting in not much change.

In Australia, men have killed 12 women in the past 18 days, and recorded sexual assaults have risen 12 years in a row.

On a global level, we saw the court case in France where 92 men in a small village raped a 70-year-old woman, and Americans electing a convicted rapist as President.

If you’re a man, you may feel very conflicted about the idea of an International Men’s Day. Imagine walking to HR and asking for an IMD event. Should there even be a day for you?

My take: if there’s a day for donuts, why shouldn’t there be one for men? And I mean this without any facetiousness. Don’t worry. I’m not going to start playing the world’s smallest violin, nor am I encouraging a celebration.

If you’ve met me, you know I’m not a fan of “days” in particular, but I believe they can be a great moment in time to mobilise us all, take stock and shine a light.

So, since I’m writing this, let me be the one to shine a light on the invisible man, the lack of conversations about masculinity and why this is incredibly important for all of us—and in particular men—who work in an industry that contributes to popular culture.

In our industry, the absence of male voices on all things equality has never been more visible. Take a look at the discourse around the lack of female roles in our creative departments sparked by the Campaign Brief furore—there were endless conversations between women in the industry. And lots of them were very public.

A conversation about equality driven by women, as per usual.

The few men who stepped into the light and spoke publicly were the same few who usually speak up. And they spoke with courage and conviction.

There were also men who had to make statements because they were directly impacted. Some of them chose the predictable route of blaming the system itself, washing their hands of accountability by explaining the status quo. We tried, you know.

Other than that, it was tumbleweeds. The men were nowhere to be seen. Invisible.

Celebrated on paper, but mute in the conversation about that paper.

Looking at it with an empathetic lens, one could say that the gender equality conversation is fraught with risk when you are a man. You may get it wrong, you may be seen as virtue signalling, or your contribution on what is falsely perceived as a ”women’s issue” doesn’t matter.

A more cynical person could say that being on the right side of history should be incentive enough to take that risk, but that completely ignores the underlying system that is in place—a system where men’s behaviour is heavily policed by other men, as explained by the Man Box study.

The Man Box is the set of beliefs within and across society that place pressure on men to act a certain way. It found that social pressures around what it means to be a “real man” are strong in Australia, and impact on the lives of most men from a very young age. Two-thirds of young men said that since they were boys, they had been told a “real man” means engaging in an established set of behaviours.

This is no different for men in our industry who may want to opt for paternity leave, but feel it could give an unfavourable impression to their bosses. Or who want to pick up the kids and get “Isn’t that your wife’s job?” as an answer.

Create Space data tells us that anyone who isn’t a white hetero normative male is a minority in leadership positions. Why? Because they behave differently and do not match the outdated and ingrained image of what a successful leader looks like. If you want to climb the ladder, first you have to fit in the box.

As I write this, the formerly powerful radio/tv host, career misogynist and equal opportunity abuser Alan Jones is arrested on indecent assault charges against teenage boys and men. A man so desperately in need of affirming his dominant masculinity, that he always felt the need to not only hide his sexuality but also publicly bully two female prime ministers.

The concept of hegemonic masculinity is deeply rooted in our culture. Men are stoic, play with balls, eat red meat, and drink beer. They are strong, they have testosterone, they provide, they do “men’s work” like trades, or they have a successful professional career. They don’t become a nurse or a teacher, because caring is soft, and that’s what women are. And we as marketers and creatives have long used these narratives as a tool to sell to men.

In June 2023, we embarked on an 18-month research piece in partnership with The 100% Project, with full study results launching in February 2025. The aim is to bring awareness to the various masculine archetypes that currently exist in Australian media, and then look at how these stereotypes influence not only the overarching view of what masculinity is, but how it manifests in everyday life.

We know from the preliminary results that men are frustrated by the one-dimensional media portrayals, which lack the depth and variability of real-life experiences, making them feel misunderstood and misrepresented. They feel unseen.

Also, through the years of work we’ve done with Fck The Cupcakes and White Ribbon, we’ve heard time and time again about the disguises men are conditioned to wear and the issues that arise when men feel forced into the shadows.

Looking at the men’s mental health epidemic, we know that outdated, patriarchal and narrow definitions of what a man should be are harming men en masse.

So, here we are. We haven’t achieved equality for women, misogyny is on the rise and, at the same time, we’re seeing men’s mental health problems grow, manifesting not just in men’s violence against women and children, but increasingly in violence against themselves, including suicide, self-neglect and substance abuse.

Three quarters of deaths by suicide are men. And, worryingly for future generations, 25% of Australian teenage boys see Andrew Tate as a role model. We also know from this GWI data that out of all audiences, it’s Gen Z men who disagree most with the statement that “all people should have equal rights”.

This speaks volumes, yet men are more silent than ever.

A lack of visible positive role models, and a lack of connection have sent men to places that are mostly toxic. And it’s easy to see why. In an increasingly complex and chaotic world, young men don’t quite know where they belong anymore. They are disenfranchised, disillusioned and, just like everyone else, they have the need to belong.

The manosphere is that space of belonging. It’s tribal, there are hierarchies of who is an “alpha” and a “beta”, and it peddles a magic bullet solution of how to dominate others, and how to get rich and ripped quick with steroids and crypto. It’s where “women belong in the kitchen” and phrases like “your body, my choice” are inspired. It’s a horrible space, but belonging feels great in a world where real connection is increasingly rare.

Clearly, we’re not doing a good enough job championing a more sustainable and healthier version of masculinity, one that ultimately leads to more success than the unsustainable construct of the alpha male.

To counter this, we need better, more visible role models to start conversations about masculinity with our future generations. We need them to champion healthier versions of masculinity that lead to success that isn’t defined by dominating others, but instead gives meaning.

Difficult? Sure. But as marketers, we can actually make a difference.

We are a $50 billion+ industry perpetually producing an enormous amount of content and stories that have a huge influence on gender roles. What we choose to create has the power to make the invisible, visible.

Is this complex? Yes.

Is it fraught with risk? Yes. A lot of it.

But if it’s done right, it can drive societal change at scale.

Assuming signalling a paradigm shift isn’t incentive enough for you, let me rephrase the solution in more commercial terms:

Two in three marketers believe there is a need to change the way they communicate with young men, but this is a complex task that requires a lot of nuance. Currently, only single-digit percentages of advertising show gender in non-traditional roles in 2024 (WARC data).

But that is only a small part of the issue. Showing gender in non-traditional roles is not a panacea, in fact it’s mostly a tokenistic approach that further alienates the men who want to live up to some of the facets of a traditional masculinity, but not all of them. There is a lot of nuance required that goes beyond slapping a same sex couple, a transgender character or a mixed ethnicity family into ads.

For those willing to actively invest and connect with men, there is a massive upside.

By 2030, the predicted value of the Australian retail industry is set to reach $545 billion and 48% of this value is estimated to be spent by Gen Z and Millennials. Assuming equal spend across genders, this means $130 billion in male spend is up for grabs.

So today, on International Men’s Day, consider talking about what you’re going to do on the topic of healthy masculinity, as a parent, as a mate, and in business.

And, if you’re a “good man” reading this, I’d also encourage you to ask yourself what your definition of “good” is. Are you using the word as a proxy for being non-violent and not causing harm, or are you actively driving change forward?

If it’s the former, consider this: Non-intervention might not make you a “bad” man, but it might just make you another invisible one.